Most Californians say it is important to plan for end-of-life care but far fewer have done so, a gap that means they may not spend their dying days the way they wish.

According to a survey released Tuesday by the California HealthCare Foundation, 70 percent of Californians said they would prefer to die at home, and, in the case of an advanced illness, 67 percent said they would prefer to die a natural death if their heartbeat or breathing stopped.

But they often haven’t communicated those wishes to their loved ones or doctors.

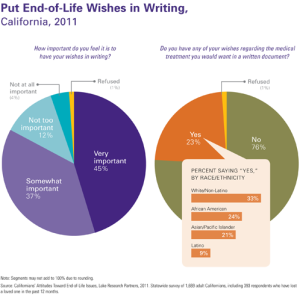

For example, while 82 percent of Californians say it is important to put their end-of-life wishes in writing, only 23 percent have done so, and only 7 percent of Californians say their doctor has talked with them about their preferences.

It was the idea of Medicare reimbursing doctors for talking with their patients about their wishes and options at the end of life that sparked the “death panel” controversy during the health reform debate. The survey found that the politically-charged idea of paying doctors to talk with their patients about end-of-life options had broad support among Californians regardless of their political affiliation.

Sixty percent of Californians said it is “extremely important” that their family not be burdened by tough decisions about their care, but 56 percent have not communicated their end-of-life wishes to the loved one they would want to make decisions on their behalf.

Nancy Berlinger, a research scholar at The Hastings Center, a bioethics research institute, said that the survey’s findings are consistent with other polls. She said it can be difficult for people to think about the end of their lives, which is part of why it’s so important that the health care system has incentives in place that allow medical providers to open the conversation.

And if the conversation happens ahead of time, it can take into account not just the kinds of medical interventions a patient does or does not want but also the kind of life they want to lead—and how their wishes may change over time, according to Berlinger.

“You can work with a patients to say ‘Here’s a care plan that works with your preferences and values,'” she said.

Diane E. Meier, director of the Center to Advance Palliative Care at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine, said that framing the discussion in terms of how a patient wants to live is critical, especially in the case of a serious illness that may last for years.

“People want to live as well as they can as long as they can, and they want help with that,” she said.

Mark D. Smith, president and chief executive officer of the California HealthCare Foundation, believes that conversations about the end of life also need to be documented and accessible to any medical provider a patient comes across, since their family doctor or loved ones may not always be available.

The foundation promotes the use of the Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment, a standardized medical order form that indicates what types of treatments a seriously ill patient does not want.

The poll on end-of-life care, conducted by Lake Research Partners for the California HealthCare Foundation, surveyed 1,669 Californians 18 and older, including 393 respondents who have lost a loved one in the past 12 months, from Oct. 26 through Nov. 3, 2011 and has a margin of error of 2.4 percentage points.

On Tuesday, the Foundation also released Tuesday a report on the state of palliative care in California hospitals.